Seahawks drafting Frank Clark lets fans down where NFL has let society down for a long time

Domestic violence charges filed against athletes used to be swept under the rug. They were a footnote in a scouting report. The value of a player on the field simply outweighed the ethical and moral dilemma of having him as a face of your franchise.

Things were simpler then. Our rooting interests were more linear, and required less parsing of information and morality. Just win, baby. Or something like that.

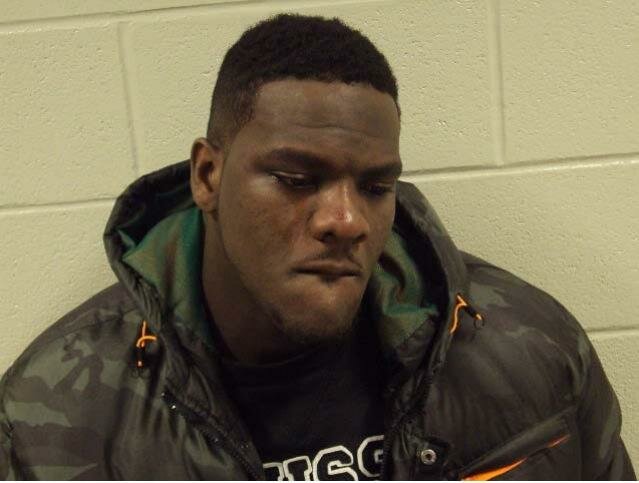

On Friday the Seahawks drafted Frank Clark, and Frank Clark has an ugly domestic violence incident in his past. He beat up his girlfriend in a hotel room in Ohio, and some six months later he was drafted by the Seahawks in the second round of the NFL draft. Fans are outraged at the incident, and outraged that they’ll be forced to root for a team with a player who has these issues in his past, or basically to quit watching the NFL.

Clark was dismissed from his Michigan team for these incidents, but he’s still got a chance to become a star on an even larger stage on the Seahawks defensive line.

For as long as I know of sports history, which is probably a modest amount, sports have been a reflection of social enlightenment and change. Sports are far from an idyllic driver for social change, and often fans aren’t able to unpack their sports fandom enough to see past these events. And this is what makes them a great reflection. Otherwise good people are resistant to change, and for sports fans this is amplified because fans often have a stake in the performance of the perpetrator, and little stake in the health and safety of the victim.

Sports are a bad substrate for justice. But they don’t necessarily have to be.

The Seahawks drafted a past domestic abuser. The inner conflict fans are feeling is a sign of progress of the average sports fan, not undue inconvenience.

But the Seahawks already tried to lure Greg Hardy – a defensive lineman with a similar, or perhaps more horrific history of domestic violence – to boost their pass rush. That they’d draft a player with this history isn’t surprising.

The Seahawks front office has a job, and that job isn’t to pass moral judgment on players per se. Their job is to win games, and up until recently, the NFL has done very little to disincentivize teams from drafting players with these types of character concerns. This doesn’t exonerate the Seahawks by any means, but when given the option of winning or being terminated from employment, many people have done a lot worse than employing violent criminals, unfortunately.

On this same weekend, Jameis Winston, who has a rape allegation and several other less outrage-inducing transgressions under his belt was drafted first overall. Millions of people spent hundreds of millions of dollars to watch Floyd Mayweather, who has a domestic violence background himself, compete in a violent arena with Manny Pacquiao.

Seahawks fans can be outraged, and they are right to be. But the outrage over domestic violence as an issue shouldn’t be localized. This isn’t just a Seattle Seahawks issue. The NFL proved last year that their stance on issues is driven very strongly by their dollars. The NFL became a laughingstock when Roger Goodell opted to suspend Ray Rice for two games after knocking his then-fiancee out in an elevator. Only once the video was released, and the horrific details of the case were paired with a visual reminder of the lunacy of the NFL’s light sentence, did the NFL extend the suspension.

As a pillar of the local community, the Seahawks owe it to their fans to carry a torch for morality. They let us down. But to a much larger degree, the NFL needs to continue to make it harder for people to become millionaires and icons after a history as violent criminals.

Of course, maybe Frank Clark has changed. Maybe this was a one-time occurrence. But maybe it wasn’t. Maybe this wasn’t the first time this had happened, and maybe it’s not the last time it ever will happen.

Players who fail drug tests at the combine, or who have substance abuse issues in college, sometimes enter the NFL in the substance abuse program already. There’s no reason – apart from self-serving collective bargaining from the NFLPA, of course – that the NFL shouldn’t enter malcontent college players into their personal conduct policy.